Transfer Pricing and Captive Insurance: The Importance of Substance

Monique van Herksen , Clive Jie-A-Joen , Fan Bai | August 20, 2018

Authors' note: Monique van Herksen, Clive Jie-A-Joen, and Fan Bai work in the Financial Markets Practice Group of Simmons & Simmons LLP with a focus on transfer pricing. Any errors or admissions are those of the authors, and this article is written in their personal capacity.

What Is Transfer Pricing, and Does It Apply to Captive Insurers?

Transfer pricing is the number one international tax issue facing multinational enterprises and pertains to the pricing of intercompany transactions between associated enterprises known as multinational enterprise (MNE) group entities. Intercompany transactions between MNE group entities account for a significant part of global trade and include the following.

- Production and sale of tangible goods (e.g., raw materials and final goods)

- Provision of services (e.g., head office services, procurement services, and research and development services)

- Transfer (e.g., sale or licensing) of intangibles

- Provision of a loan/guarantee or other financial transactions (e.g., cash pooling and provision of insurance coverage by a captive insurance company to group entities)

For tax purposes, transfer prices should be determined in accordance with the so-called arm's-length principle. This means that the conditions of intercompany transactions within an MNE group should be consistent with the conditions that independent enterprises would have agreed on in comparable transactions in comparable circumstances. The OECDTransfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations ( Guidelines) provide guidance for applying the arm's-length principle. (OECD is the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.)

Notably, the arm's-length principle also applies to captive insurance and whether insurance premiums paid to a captive insurance company are arm's length or not.

What Is the Consequence for Incorrect Transfer Pricing?

Incorrect transfer pricing can lead to costly tax audits, double taxation, penalties, and reputational damage. Consequently, in recent years, transfer pricing concerns have risen beyond tax departments and into boardrooms. Many stakeholders within MNEs and other stakeholders, such as the general public, the European Commission, politicians, and journalists are paying attention to transfer pricing as well.

Transfer pricing aspects have also been litigated. Of note for captive insurers, in a number of cases, tax authorities sought to decrease captive insurance company profits by arguing the limited functional and risk profile of the captive insurer. These cases, two of which will be discussed in more detail later (see section on pricing insurance premiums), include the following.

-

DSG Retail Limited case (UK) 1 focused on appropriate transfer pricing methodology for a captive insurance transaction.

-

In a Dutch holiday and leisure resort group (anonymous) case, the Dutch Tax Administration unsuccessfully attempted to recharacterize the intercompany transactions under review. Nonetheless, the court found that the captive insurer's profits were too great and instead amended the captive insurer's arm's-length remuneration to a 10 percent markup for its administrative expenses. Allocation of the remainder of the captive insurer's profits went to the group's Dutch entities.

-

Another Dutch court case involved a Dutch mutual insurance company (anonymous) and the practice of applying the comparable uncontrolled price method.

The OECD Tackles Intercompany Financial Transaction and Transfer Pricing

According to the OECD website, "Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) refers to tax avoidance strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations. Under the inclusive framework, over 100 countries and jurisdictions are collaborating to implement the BEPS measures and tackle BEPS." 2

In October 2015, as part of the final BEPS package, the OECD/G20 published the report on Aligning Transfer Pricing Outcomes with Value Creation, under BEPS Actions 8–10. The report contained revised guidance on a number of key areas, including transfer pricing issues. The report also mandated follow-up work to develop guidance on BEPS actions 8–10 3 as part of a larger effort to "equip governments with domestic and international instruments to address tax avoidance, ensuring that profits are taxed where economic activities generating the profits are performed and where value is created." 4

In July 2018, the OECD released a discussion draft for public comment (draft) containing additional guidance on the application of the BEPS Actions 8–10 mandate ("Assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation"). The guidance surrounds transfer pricing aspects of intercompany financial transactions that represent the last missing piece of the transfer pricing portion of the OECD's project on developing measures for tackling BEPS.

The existing OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines will eventually be updated with a financial services chapter providing specific guidance on transfer pricing aspects of intercompany financial transactions, such as treasury functions, intragroup loans, hedging, cash pooling, financial guarantees, and captive insurance. The OECD invites comments on the draft by September 7, 2018.

Importance of the Discussion Draft for Captive Insurance Companies

Although not considered a consensus document and still in draft form, the OECD draft presents some highly relevant guidance for taxpayers engaged in intragroup financial transactions with related taxpayers. This also includes guidance on the transfer pricing aspects of captive insurance companies.

In fact, some countries may already be following certain guidance contained therein, and some of the guidance seemingly reflects aspects that have been the subject of litigation in different countries.

The draft contains specific guidance for accurate determination ("accurate delineation") of intragroup financial transactions based on economically relevant characteristics, including the following.

-

Contractual terms

-

Functions performed (including assets used and risks assumed)

-

Characteristics of financial products or services

-

Economic circumstances

-

Business strategies

For captive insurers affording insurance coverage to related group entities, accurate delineation means that any economically relevant characteristic from the above list should be analyzed in detail to better understand and characterize the intercompany provision of insurance coverage.

Subsequent to accurate delineation, the arm's-length nature of the transfer prices for an intercompany transaction can be tested or determined. According to the draft, each type of financial transaction has its own specific characteristics and transfer pricing issues. Ergo, the draft discusses pricing and the available pricing methodologies for each type of transaction. While the methodologies presented are unsurprising, the draft does not supply explicit guidance for applying such methodologies.

In the next section, we present some of the draft's key takeaways for captive insurance companies.

Application of Accurate Delineation Analysis to Captive Insurance

As mentioned earlier, the transfer pricing analysis of captive insurance starts with an accurate delineation of the captive insurance arrangement. This means that a detailed analysis is required based on the following characteristics.

-

Contractual terms of the transaction, which may describe the allocation of responsibilities, obligations and rights, assumption of identified risks, and pricing arrangements of the captive insurance transaction

-

Functions performed, assets used, and risk assumed by the respective associated enterprises (i.e., the captive insurance company and related insured parties)

-

Specific characteristics of the captive insurance arrangement

-

Economic circumstances of the parties and the market

-

Business strategies

As stated in the draft, one option for managing risks within an MNE group is to consolidate risks 5 through a captive insurance company, which is a group member that provides insurance-type services mainly or exclusively to other group members. Likewise, the MNE group may decide to obtain insurance from an independent insurer(s) or otherwise retain and finance the risk with its own funds.

The draft also recognizes reinsurance captives under a fronting arrangement in which an independent regulated insurer (i.e., the fronting company) issues an insurance policy directly to the insured MNE group members. Then, under a reinsurance agreement, the fronting company reinsures all or most of the risk through the captive reinsurer that is part of the MNE group.

The draft defines insurance based on Part IV of the 2010 Report on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishment as follows.

As a general matter, the insurance business is the business of accepting obligations or liabilities in respect of uncertain losses arising from the realisation of events outside the control of the insured. Insurance businesses are able to do this by pooling the potential losses of many risk-averse persons via the payment of an amount by the insured to the insurer, called a premium…. In consideration of the payment of the premium, when the insured incurs a loss or a specified event occurs, he, she or a beneficiary is indemnified for the amount of the value of his or her loss or receives an agreed payment or service.

The draft differentiates between the following insurance risk.

-

The specific risk to which the insured party is exposed that is insured and controlled by the insured party

-

The insurance risk taken on by the insurer through providing insurance coverage to the insured party

When evaluating transfer pricing for a captive insurance transaction, a common concern for tax authorities is whether or not the transaction actually constitutes insurance as defined in the applicable tax code. In other words, it is whether an insurance risk exists and whether the insurance risk has actually been contractually allocated and transferred to the captive in accordance with the principles of Chapter I of the Guidelines (e.g., the six-step risk allocation framework).

Note: Draft comments are requested surrounding what specific risks the policy issuer (the captive insurer) must assume in order to earn an insurance profit.

From a transfer pricing perspective, the MNE group entity assuming insurance risk should expect a higher return. Therefore, it is important to evaluate which MNE group entity assumes what risk. In this respect, a captive can only assume the insurance risk that is contractually transferred to it, and thus it is entitled to the expected return associated with the insurance risk assumption, if it can control the risk and has the financial capacity to assume the assigned risk.

As touched on previously, accurate delineation requires a careful determination of who controls the insurance risk and whether or not financial capacity exists to bear risk. Control of the insurance risk means that the captive should be capable of the following.

-

Making decisions to take on, lay off, or decline a risk-bearing opportunity, together with the ability to carry out that decision-making function

-

Making decisions on if and how to respond to the risks associated with the opportunity, together with the ability to carry out that decision-making function

The allocation of insurance claims, premiums paid, and investment returns may all be impacted if a captive is found to not control the contractually transferred insurance risk.

Financial capacity to assume risk means that the captive has access to adequate funding in order to take on risk or to reduce risk, to pay for the risk mitigation functions, and to bear the consequences of risk materialization. In this respect, the captive should have adequate personnel to manage the insurance risk assumption.

Note: Accordingly, the OECD also asks for input around what control functions are needed for the captive to assume the insurance risks and whether or not the captive can control risk in the case where the underwriting function is outsourced.

Is the Captive Transaction Actually Insurance?

The draft observes the following with respect to determining whether or not the captive transaction is actually an insurance transaction.

-

The presence of all six of the following required indicators.

-

There are diversification and risk pooling in the captive insurer.

-

The captive insurer improves the economic capital position of the MNE group because either the group risk is diversified by including non-group risks or part of the insurance risk is reinsured with third parties.

-

There is application of a regulatory regime governed by a regulator.

-

Without the captive insurance, the risk would have been insured externally.

-

The captive insurer has the requisite skills and experience including employees with underwriting experience.

-

The captive has the real possibility of incurring losses.

-

-

The captive should assume the insurance risk, which implies that the captive controls the insurance risk and has the financial capacity to assume the insurance risk. The captive should be able to satisfy claims if a risk materializes. Therefore, the captive should employ personnel who have the relevant capabilities to do so and who are able to perform decision-making functions.

-

The presence of risk distribution, which is the pooling of a portfolio of risks to reduce the impact of individual claims, is necessary for the existence of a true insurance business. In addition, the insurer has a capital reserve based on regulatory and rating agency requirements.

-

Business reasons for using a captive include the following.

- Stabilizing the premiums paid by MNEs

- Benefiting from tax and regulatory arbitrage

- Obtaining access to reinsurance markets

- Keeping the insurance risk within the MNE group is more cost effective

Under the OECD Guidelines, tax authorities may disregard an intercompany transaction for tax purposes when the arrangement differs from a reasonable commercial transaction between associated enterprises, thereby preventing the determination of an acceptable price to both parties.

Further, the draft provides that when a captive is used to insure risks for difficult-to-obtain commercial insurance coverage, tax authorities should question the commercial rationale behind such an intercompany arrangement and may disregard the captive insurance transaction for tax purposes.

- As regards reinsurance captives, there are cases in which an MNE group involves a third-party regulated insurer (fronting company) to issue insurance policies for related insured entities or customers of the MNE group. The fronting company subsequently reinsures all or a part of the risk through the reinsurance captive that is part of the MNE group.

A third-party fronting company may be needed because the captive reinsurer does not have the required licenses or regulatory approval to directly insure its own risks for a specific insurance coverage or in a specific country or jurisdiction. The draft suggests that such fronting arrangements involve controlled transactions that are complex to price.

Determining the Arm's-Length Transfer Price for Captive Insurance Transactions: Pricing Insurance Premiums

The draft discusses the following approaches for pricing insurance premiums.

The CUP Method

The application of the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method is based on comparable arrangements between independent enterprises. The CUP method "compares the price charged for property or services transferred in a controlled transaction to the price charged for property or services transferred in a comparable uncontrolled transaction under comparable circumstances." 6 When using the CUP method, comparability adjustments are required to account for differences between the captive insurance transaction and available market transactions. The draft refers to comparable arrangements based on transactions between the captive insurer and third-party customers.

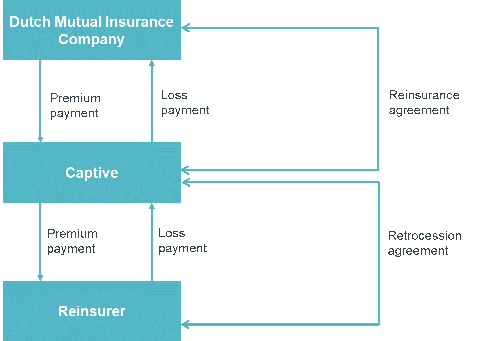

The practice of applying the CUP method is demonstrated through a Dutch court case involving a Dutch mutual insurance company (insurance company) that initially reinsured most of the risks it underwrote through several external reinsurers. The insurance company restructured its business model by setting up a Swiss subsidiary (captive) and subsequently entered into reinsurance agreements with the captive (replacing the external reinsurers) in exchange for paying insurance premiums to the captive. The captive reinsured most of its risks with third-party reinsurers. The captive did not employ its own personnel but made use of the services of a third-party Swiss reinsurance broker. The figure below shows an overview of the transactions.

The premiums paid by the insurance company to the captive were higher than the premiums it paid to the third-party reinsurers. The Dutch tax inspector held that the terms and conditions of the reinsurance agreements between the insurance company and the captive would have been different if agreed upon between independent parties. A court-appointed industry expert agreed with the Dutch tax inspector's application of the CUP method with the following findings.

The expert found it unclear why [the insurance company] paid a higher net premium to [the captive] than it would have paid external reinsurers. Even when considering additional captive expenses, the expert found that the captive adds little value in the chain. Regarding an arm's-length price, the expert found that one could use the net premium paid by [the captive] to the external reinsurers. Also, the expert found that the costs of the intermediary role are known, and could be charged to [the insurance company] on a cost plus basis.

However, the industry expert did not agree with the Dutch tax inspector's suggestion that because of the captive's weak capital position (that is, the limited amount of capital it had available to satisfy a claim) and its low credit rating, the expectation is the net premium paid would be lower than the premium that would have been paid to a reinsurer with a better capital position. According to the expert, a low credit rating should not impact the premium if the captive in turn reinsures the risks.

In the end, the court agreed with the Dutch tax inspector that the terms and conditions of the reinsurance agreement entered into between the insurance company and the captive differed from the terms and conditions that would have been agreed on between independent enterprises and ruled that a large part of the profits of the captive's insurance activities were to be allocated to the Netherlands. The court ruled that an arm's-length remuneration for the captive would be a return on equity of 7.5 percent in addition to a cost-plus markup.

In addition to the CUP method, the draft suggests the following approaches to pricing insurance premiums.

-

Perform an actuarial analysis to determine a premium that covers the insurer's expected claims losses, underwriting and administrative costs, and claims handling expenses. The calculation should contemplate a profit to make available a return on capital while also accounting for any investment income.

-

A comparable uncontrolled price can be determined based on considering the arm's-length profitability of the captive based on a two-step approach.

- Identify the captive's "combined ratio," which is a ratio used to measure the underwriting profitability (premiums, less claims, less expenses) of insurance companies.

- Add an investment return on capital, taking into account the capital of the captive and investments made by the captive in related party investments, such as intragroup loans. The draft provides that the capital required for a captive is lower than that required for an unrelated insurer because of regulatory and commercial factors.

Note: we would like to see concrete examples from the OECD to illustrate the above approaches for pricing insurance premiums.

Group Synergy Benefits

The draft also discusses the case where group synergy benefits are achieved when MNE policyholders pool their risks in the captive insurer, which in turn reinsures the risk in the external reinsurance market (thereby achieving lower premiums through collective negotiations). The draft provides that the synergy benefits should not be accrued and allocated to the captive and instead should be allocated to the MNE policyholders in the form of lower premiums after providing the captive with an arm's-length remuneration for basic services rendered (in line with the guidance on group synergies in Chapter I of the Guidelines). This is consistent with Chapter I of the Guidelines, which provides that synergy benefits are normally not available to independent enterprises. Such group synergies should generally be allocated to MNE group members in proportion to their contribution to creating the synergies.

Agency Sales

Additionally, the draft addresses agency sales, where a retail sales agent is involved in arranging the sale of insurance contracts. The transaction may result in very profitable insurance contracts entered into between the captive insurer (or the fronting company) with third-party customers at the point of sale of a product (e.g., at a retail company). The above scenario contemplates that an active insurance market exists for the particular insurance risk.

In such a scenario, the draft puts forth that the high profit is due to an advantage. The advantage, the draft suggests, is the sales agent's intervention at the point of sale, where the MNE group company controlling the point of sale involves an alternative agent to provide insurance policies. The draft concludes that without having an alternative agent at the point of sale, the captive faces a disadvantage. The draft concludes that the captive should earn an arm's-length return consistent with the benchmarked return for insurers, while the residual profit should be allocated to the group entity with the point-of-sale advantage.

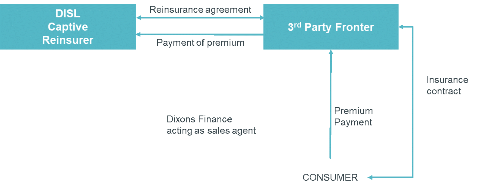

The transfer pricing aspects of the agency sales scenario were litigated in the DSG Retail Ltd (DSG) case where the special commissioner ruled in favor of Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (HMRC). DSG, a UK retailer of electrical goods, offered its customers, at the point of sale, extended warranties to cover the cost of repair beyond the manufacturer's standard warranty period. Dixons Finance acted as the sales agent. The customers concluded insurance contracts directly with an unrelated fronting company, and subsequently this fronting company entered into a reinsurance agreement with a captive insurer (DISL) domiciled in the Isle of Man.

The special commissioner found that DISL's activities were routine in nature relative to DSG. The taxpayer referred to various commission comparables to substantiate the commission paid to the sales agent; however, these were rejected by the special commissioner because of comparability defects (e.g., no similar point-of-sale advantage, old comparable, and the property insured was not comparable).

The taxpayer subsequently suggested the use of the transactional net margin method (TNMM) to evaluate the DISL's profitability based on the return on capital earned by an independent enterprise, referred to as D&G in the court case, that provided extended warranty products to small retailer customers at the point of sale. D&G also engaged in insurance activities, which included claims and policy administration.

Ultimately, D&G was rejected as a TNMM comparable for DISL's profitability because of D&G's different functional profile and bargaining power (the D&G retailers themselves were not able to offer the warranties to customers) and the case was eventually settled out of court. The figure below shows an overview of the transactions.

Concluding Remarks

The discussion draft on the transfer pricing aspects of intragroup financial transactions covers treasury functions, intercompany loans, hedging, cash pooling, financial guarantees, and captive insurance. The draft acknowledges that each type of financial transaction has its own specific characteristics and transfer pricing issues.

Key takeaways in the draft for captive insurance companies include the following.

-

A common concern in evaluating transfer pricing for a captive insurance transaction is whether the transaction relates to and qualifies as rendering insurance. In other words, whether the insurance risk has actually been contractually allocated and transferred to the captive.

-

The presence of risk distribution, which is pooling a portfolio of risks to reduce the impact of individual claims, is necessary for the existence of a true insurance business.

-

The assumption of risk is important for captive insurance transactions, since the party that assumes a risk will expect to receive higher returns. The question becomes whether or not a captive assumes the insurance risk that is contractually transferred to it. From a transfer pricing perspective, the captive is assuming a risk that is contractually transferred to it if it controls the risk and has the financial capacity to assume the risk.

-

Group synergy benefits created by deliberate concerted group actions of MNE policyholders and the captive insurer through risk pooling within the MNE group in the captive, which in turn reinsures the risk in the open market, should be shared with the MNE policyholders through reduced premiums. The captive should receive an arm's-length remuneration for basic services rendered.

-

The draft discusses several approaches for pricing insurance premiums, including actuarial analysis, applying the CUP method, and considering the arm's-length profitability of the captive by examining underwriting profitability and assessing investment return.

-

In case a related sales agent is involved in arranging the sale of insurance contracts, the draft concludes that the captive should earn an arm's-length return consistent with the benchmarked return for insurers, while the residual profit should be allocated to the group entity with the point-of-sale advantage.

If anything, the draft indicates a need for MNEs to review their captive insurance arrangements by accurately delineating the specific transactions and evaluating the transfer pricing approaches. Potential transfer pricing risks can be managed or reduced by preparing additional transfer pricing documentation, updating substance, or other related actions.

Taxpayers should consider providing comments to the draft as requested by the OECD.

- J. Reyneveld and M. Bonekamp, "Netherlands—Recent Case Law on Captive Insurance Companies: What Is the Right Transfer Pricing Approach?" International Transfer Pricing Journal, Vol. 19, No. 1, January 5, 2012.

- "Base Erosion and Profit Shifting," OECD.org, Center for Tax Policy and Administration.

- "OECD Releases New Guidance on the Application of the Approach to Hard-to-Value Intangibles and the Transactional Profit Split Method under BEPS Actions 8–10," OECD.org, Tax, Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, June 21, 2018.

- "BEPS Actions," OECD.org, Center for Tax Policy and Administration.

- According to Aon's 2015 Global Risk Management Survey, the top 5 risks written in captives are (1) property damage and business interruption, (2) general/third-party liability, (3) employers liability/workers compensation, (4) product liability, and (5) professional indemnity/errors and omissions liability.

- Transfer Pricing Methods, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD.org, July 2010.

Monique van Herksen , Clive Jie-A-Joen , Fan Bai | August 20, 2018